I need to tell you about one expensive mistake I made in this business.

Early on, I had the opportunity for commercial laundry work. A hotel approached me about doing their laundry. I was so focused on landing the account that I bid the work too low. But I figured it would be fine because of the volume. "Sure, the margins are thin," I told myself, "but think about all those pounds we'll be processing. We'll make it up in volume."

I was wrong.

Instead of "making it up," I just lost money faster. The more laundry we processed, the bigger the hole we dug. It took me a couple months to realize what was happening and a few more to fix it.

Here's what frustrates me. I still hear this exact advice many places in our industry. Facebook groups. Social media posts. Even from time to time at industry events. “Price it competitively and make it up in volume." "Land that big account even if margins are tight the volume will save you."

Bad math is bad math, no matter how many social media likes it gets.

And right now, this bad advice is draining operators who don't realize they're being led down the same path I took.

The Math Doesn't Lie (Even When You Want It To)

Let me show you how this trap works with real numbers.

Say you bid commercial laundry work at $1.00 per pound. Sounds competitive, right? Maybe even attractive to potential clients.

Now let's look at what it actually costs you to process each pound. These are example numbers that will vary depending on your market, equipment type and mix, utility rates, and operational setup, but the principle remains the same:

Your Variable Costs Per Pound:

- Water: $0.15

- Electricity and gas: $0.25

- Detergent and chemicals: $0.20

- Direct labor (the person actually processing): $0.50

Total variable cost: $1.10 per pound

You're losing $0.10 on every single pound before you even think about rent, equipment, insurance, or any other expense.

Now here's where the "make it up in volume" trap snaps shut:

- Process 500 lbs/week: Lose $50/week = $2,600/year

- Process 2,000 lbs/week: Lose $200/week = $10,400/year

- Process 5,000 lbs/week: Lose $500/week = $26,000/year

More volume doesn't fix the problem. It multiplies the problem.

The math is brutal, but it's honest. If you're losing money on variable costs per pound, every additional pound you process just digs the hole deeper.

This Isn't Just a Laundry Problem

Before you think this only happens in our industry, let me show you how this same fallacy destroyed billion dollar companies.

MoviePass is the poster child for this disaster. They charged customers $9.95 per month for unlimited movies while paying theaters $9 to $15 for every single ticket. More subscribers didn't create profitability. It accelerated their path to bankruptcy. They burned through $40 to $45 million every month before collapsing entirely.

The restaurant industry has watched countless operators make the same mistake. They undercut competitors on pricing, thinking foot traffic will save them. Instead, they discover that their "popular" menu items—the ones everyone orders—are actually losing them money on every plate. Restaurant consultants call these "plow horses": popular with diners but unprofitable for the business.

The dot-com bubble was full of these stories: Pets.com lost $0.26 on every $1 in sales. Kozmo.com lost money on every delivery. Webvan raised $800 million and burned through every penny.

The pattern is always the same: negative unit economics multiplied by scale equals catastrophic losses.

Let's Talk About Costs Like We’re in 5th Grade

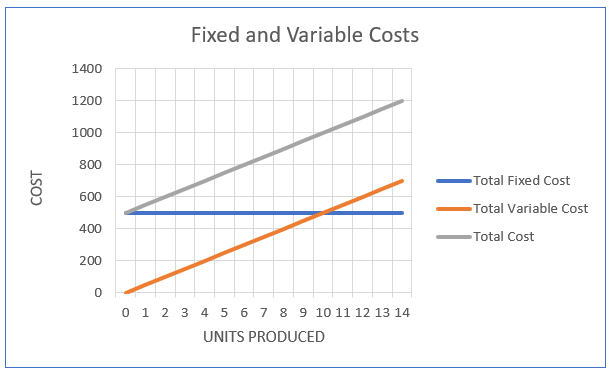

Understanding the difference between variable and fixed costs is what saves you from this trap.

Variable Costs: These Go Up With Every Pound You Process

Think of variable costs like this: every time you wash a pound of laundry, you have to pay for these things.

- Water: The more laundry you wash, the more water you use. If you don't wash laundry, you don't use water.

- Electricity and gas: Running washers and dryers costs money every single time.

- Detergent: Each load needs soap. More loads = more soap = more cost.

- Labor: If you're paying someone $15/hour to process laundry, and they can handle 30 pounds per hour, that's $0.50 per pound in labor.

Variable costs are like buying gas for your car, the more you drive, the more gas you need.

Fixed Costs: You Pay These Whether You Wash 10 Pounds or 10,000 Pounds

- Rent: Your landlord doesn't care if you processed 100 pounds or 5,000 pounds this month. The rent is the same.

- Equipment payments: Whether your machines sit idle or run constantly, the loan payment is due.

- Insurance: Same amount every month.

- Base utilities: You pay a minimum even if the store sits empty.

- Salaries: If you have full-time staff, you pay them whether it's busy or slow.

Fixed costs are like your car payment, you owe it whether you drove 10 miles or 1,000 miles this month.

Here's the critical part: Volume CAN help you cover fixed costs by spreading them across more pounds. But volume CANNOT fix negative variable costs. If you're losing money on variable costs, more volume just means you lose money faster while ALSO failing to cover your fixed costs.

When Volume Actually DOES Work (Let's Be Fair)

I'm not anti-volume. I love volume when it's priced correctly.

Volume strategies are legitimate and profitable when three conditions exist:

1. Positive Contribution Margin

Your price per pound must be higher than your variable costs per pound. That difference is called your contribution margin, and it must be positive.

Example of volume working correctly:

- Price: $1.80/lb

- Variable costs: $1.20/lb

- Contribution margin: +$0.60/lb

Every pound you process generates $0.60 that can go toward covering fixed costs. Once you've covered fixed costs, every additional pound is pure profit.

2. High Fixed Costs to Spread

If you have $200,000 per year in fixed costs (equipment, rent, salaries, etc.), volume genuinely helps. With a $0.60/lb contribution margin, you need to process 333,333 pounds per year to break even. That's about 6,410 pounds per week.

Every pound beyond that break-even point generates $0.60 in profit. At 10,000 pounds per week, you're making $2,156 profit per week, or $112,000 per year.

Volume is your friend here because your unit economics are positive.

3. True Economies of Scale

As you grow, you might negotiate better rates from suppliers, invest in more efficient equipment, or improve processes that genuinely reduce your variable cost per pound. These are real economies of scale.

But here's what's NOT an economy of scale: hoping that somehow, magically, processing 5,000 pounds per week will cost less per pound than processing 500 pounds when your processes, equipment, and supplier contracts haven't changed at all.

The Volume Reality Check Nobody Talks About

Even if you price correctly for volume, you need to answer two brutal questions:

Question 1: Do you actually know what volume you need?

Some operators I have spoken with can't tell me their break-even point. They don't know whether they need 2,000 pounds per week or 20,000 pounds per week to actually make money. They're flying blind, hoping volume will eventually solve everything.

Run the math:

- Calculate your total fixed costs per year

- Calculate your contribution margin per pound (price minus variable costs)

- Divide fixed costs by contribution margin = break-even volume needed

If that number makes you uncomfortable, your pricing is the problem, not your volume.

Question 2: Can you realistically GET that volume?

Say you need 10,000 pounds per week to break even. Can your market actually deliver that? Do you have the equipment capacity? The staff? The operational systems?

I've watched operators price for volume they'll never achieve. They need unrealistic scale to make their thin margins work, so they end up losing money indefinitely while waiting for volume that never comes.

Volume is not a strategy. It's a multiplier of whatever strategy you already have.

If your strategy is sound (positive unit economics), volume multiplies success. If your strategy is broken (negative unit economics), volume multiplies failure.

Thinking about the thinking of laundry:

When you realize that volume amplifies bad pricing, you stop chasing scale and start fixing your pricing.

Why Smart People Still Fall for This

If this math is so simple, why do experienced operators still fall into this trap?

It feels like action. Lowering prices to win business feels productive. You're doing something. Meanwhile, the hard work of calculating true costs, negotiating better supplier rates, improving efficiency, that's not as emotionally satisfying as "landing the big account."

It's what everyone says. When you hear the same advice repeated in Facebook groups, at conferences, from equipment salespeople, it starts to sound like wisdom instead of what it actually is, dangerous groupthink.

Sunk cost fallacy. Once you've made the commitment, invested in more equipment, hired more staff, it's psychologically painful to admit the pricing was wrong. So operators double down, convinced the next big account will finally make the math work.

The industry repeats it. When gurus post about it, when course sellers use it as a pitch ("land big accounts fast!"), when newer operators see it as conventional wisdom, the bad advice becomes self perpetuating.

What to Do This Week

Stop. Right now. And calculate your actual numbers.

Step 1: Calculate Your Variable Cost Per Pound

Add up:

- Water cost per pound (check your utility bills and machine specs)

- Electricity and gas per pound

- Detergent and chemicals per pound

- Direct labor per pound (hourly rate ÷ pounds processed per hour)

Be honest. Don't guess. Don't round down because you want the number to look better.

Step 2: Compare to What You're Actually Charging

Price per pound - Variable cost per pound = Contribution margin

- Positive? Good. Now calculate if it's enough to cover fixed costs at realistic volume.

- Negative? You're in the trap. Every pound you process loses money.

- Zero or barely positive? You're vulnerable. One cost increase and you're underwater.

Step 3: Fix It Before You Scale It

If your unit economics are broken:

- Raise your prices (yes, you might lose some clients, but you'll stop losing money)

- Reduce variable costs (better supplier negotiations, more efficient processes, different equipment)

- Walk away from contracts that don't work (painful but necessary)

Do NOT try to fix bad pricing with more volume. You cannot scale your way out of negative unit economics.

Step 4: Calculate Your Real Break-Even

Once you have positive contribution margins:

Break-even volume = Total annual fixed costs ÷ Contribution margin per pound

Now you know exactly what volume you need. Not a guess. Not a hope. The actual number.

Can you get there? If yes, pursue volume aggressively. If no, your pricing still isn't right.

The Bottom Line

The phrase "we'll make it up in volume" originated as an economics joke. It's the punchline to "we lose money on every sale, but we make it up in volume."

Economists say this sarcastically because the math makes it impossible.

When you're losing money per unit, no amount of volume fixes it. Volume just helps you lose money faster.

I learned this the hard way. I'm sharing it now so you don't have to.

The next time someone tells you to price low and make it up in volume, ask them to show you the math. If they can't prove positive unit economics, they're not giving you business advice.

They're leading you toward bankruptcy with better marketing.

That's all I got for you today.

Waleed

PS:

Echoing the thoughts of Benjamin Franklin.

Beware of little expenses; a small leak will sink a great ship.

Footnotes:

¹ MoviePass Financial Collapse and Unit Economics: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-11-17/america-s-zombie-companies-have-racked-up-1-4-trillion-of-debt

² Restaurant Menu Pricing and Food Cost Management: https://www.touchbistro.com/blog/strategies-for-pricing-a-restaurant-menu/ and https://www.netsuite.com/portal/resource/articles/accounting/restaurant-food-costs.shtml

³ Failed Dot-Com Companies Business Case Studies: https://www.adaptcfo.com/post/the-real-cost-of-growth-why-most-companies-lose-money-while-scaling

⁴ Commercial Laundry Operating Costs and Pricing Data: https://www.2ulaundry.com/how-much-does-wash-and-fold-laundry-service-cost/ and https://homeguide.com/costs/laundry-service-cost

⁵ Economies of Scale Definition and Applications: https://www.wallstreetprep.com/knowledge/economies-of-scale/ and https://corporatefinanceinstitute.com/resources/economics/economies-of-scale/

⁶ Contribution Margin and Break-Even Analysis: https://www.cubesoftware.com/blog/cost-volume-profit-analysis and https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/financemath/chapter/6-4-break-even-chart/

⁷ Fixed and Variable Costs Graph: https://www.higherrockeducation.org/glossary-of-terms/fixed-cost